This Insight is based on research conducted by the author and Susann Wiedlitzka, the results of which are extensively discussed within an academic article recently published within Terrorism and Political Violence. The original paper develops our theoretical understanding of gamification (focussing upon its ‘mechanics’) using empirical data taken from the Christchurch attack in New Zealand in March 2019. Although this blog does not discuss these theoretical underpinnings of gamification, it does provide a summary of how the attack was gamified in nature and how the data is laden with overt and more subtle overlaps with video games more generally. For more discussion of gamification, please see previous GNET Insights such as Competing, Connecting, Having Fun: How Gamification Could Make Extremist Content More Appealing, Let’s Play Prevention: Can P/CVE Turn the Tables on Extremists’ Use of Gamification?, and Video Games, Extremism and Terrorism: A Literature Survey.

The Christchurch Attack and Gamification

In March 2019, New Zealand suffered one of its deadliest terrorist attacks in history. Brenton Tarrant, a 28-year-old Australian national and self-described ‘ethno-nationalist’ and ‘eco-fascist’, murdered 51 Muslim worshippers and attempted to kill 40 more, primarily at the Al Noor Mosque and Linwood Islamic Centre, before being apprehended by police reportedly on his way to a third location. He used a number of often complimentary online and offline resources and strategies, which included: a 74-page manifesto; live-streaming his attack on Facebook; and the initiation of a thread around 10–20 minutes before the commencement of the attack on the now-banned imageboard, 8chan. These outputs were littered with various culturally relevant symbols, sayings, and other indicators, including those relating to video gaming.

Although the intersection between video gaming and (violent) extremism has existed for decades (and some research has been undertaken), our knowledge of it still remains “poorly understood.” Of the six “types of video game strategies related to extremist activity” outlined in a Radicalisation Awareness Network paper in 2020, it can be reasonably argued that our understanding of the ‘gamification’ of (violent) extremism remains particularly scant. Still, this concept has been widely associated with the Christchurch attack. Originally developed for addressing various business challenges, at its core gamification refers to “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts”. It is about “facilitating behavioural change,” and harnessing the “motivational potential of video games,” where there is the “implementation of elements familiar from games to create similar experiences as games commonly do.”

Saying that, academic literature, news articles, and investigative journalism, amongst others, have at least (mostly anecdotally) started to describe instances of extremist and violent extremist networks adopting aspects that resemble some degree of the concept. Speaking broadly, within the context of violent extremism, gamification can be thought of as either “top-down” or “bottom-up.” Top-down gamification primarily refers to the strategic use of gamification by (violent) extremist networks and organisations in order to recruit, disseminate propaganda, or encourage engagement and commitment, for example. An example of this includes Islamic State’s Huroof app which sought to gamify the teaching of Arabic to young children with the use of and references to nasheed music, guns, bullets, rockets, cannons, or tanks, arguably in a bid to reinforce commitment to Islamic State ideologies, aims, and objectives. However, this research focussed on bottom-up gamification: an approach that, contrastingly to top-down gamification, “emerges organically in (online) communities or small groups of individuals.” In terms of bottom-up gamification, as mentioned, one of the more commonly spoken about examples is the Christchurch attack where it is widely accepted that the assailant, purposefully or otherwise, included a number of gamified elements within his assault.

Findings

The findings summarised below are based on relevant data collected in relation to the attack itself. This includes an analysis of the attacker’s 74-page manifesto, live-stream video, and original post on 8chan along with, importantly, the 749 replies posted by other 8chan users before the thread was taken down. Here, the attacker is (very generally) considered to be the ‘designer’ and ‘player’ of the game and other 8chan users are thought of as ‘spectators’ and ‘observers.’

The manifesto: setting the scene

At 1:26 pm local time, the assailant updated his Facebook status linking to seven different file sharing websites that hosted his manifesto. This manifesto acts as a backdrop to the attack and, as with video games, provides a development of the character as the chief protagonist, i.e. the assailant himself, while outlining different narratives and motivations of the attack. He talks, albeit briefly, about who he is and aspects of his background, family, and upbringing. Positioning himself as an everyday and unsung “hero,” he argues, “I am just a regular White man, from a regular family. Who decided to take a stand to ensure a future for my people.” Within this, he also sets the scene for the attack, providing the narrative, or storyline, to the event, something that is often found within games and gamified experiences. He talks about Great Replacement, but in the context of invasion and protection that can be found within numerous video-gaming scenarios, whether that is an invasion by people, aliens, or zombies, for example. However, in terms of who they are “playing against,” the competitor – or in the case of Christchurch, the enemy – is cast in the manifesto among a plethora of possibilities beyond “invaders” (i.e. those who are considered to be non-White). The potential options include prominent figures perceived to be “enemies” of their race; other “race traitors” including owners and CEOs of businesses who use non-White ‘cheap labour’; and drug dealers (both legal and illegal), amongst others. The assailant chose to target Islam and specifically selected the two mosques due to several motives, including their location as they, in his own words drawing on gaming language, enabled him to target a third location as a “bonus objective.”

The live-stream video and gamification

Reports have claimed that the attacker had a range of weapons with him which included: “four crude incendiary devices, two ballistic armour (bullet-proof) vests, military-style camouflage clothing, a military-style tactical vest, a GoPro camera, an audio speaker and a ballistic style tactical helmet. He also had a scabbard with a bayonet-style knife (with anti-Muslim writing on it).” The assailant also live-streamed his attack on Facebook using a GoPro camera connected to his phone, which was mounted to his helmet. Many elements of the attack had features relating to video games and in many respects, at times, felt like a video game. The live-streaming of the attack, for example, had distinct parallels with popular ‘Let’s Play’ videos where audiences watch people play video games live. Mounting a GoPro camera to his helmet also gave the attack the feel of a First Player Shooter (FPS), a popular gaming style where the player experiences the game from the view of the character; as seen in numerous popular and widely-recognisable game franchises like Call of Duty, Halo, or Doom. The use of multiple weapons was also reminiscent of video games.

After his attack ended at the first place of worship (the Al Noor Mosque), the assailant got back into his car and made his way to the Linwood Islamic Centre. Although his live stream fortunately cut out before he reached the second location, the footage captured during part of his drive has distinct parallels with gamification and video games more widely, particularly the popular Grand Theft Auto (GTA) franchise. This included his actual driving, where he reached speeds of 130 kilometres in a 50 kilometre per hour zone, driving erratically “weaving in and out of traffic, driving on the wrong side of the road and up onto the grass median strip.” In addition, as with most GTA games, the assailant used his weapon, in this case a second shotgun, to fire out of his car at pedestrians near the first mosque. Similarly, he also attempted, unsuccessfully, to shoot the drivers of two cars he passed on the road.

The 8chan thread

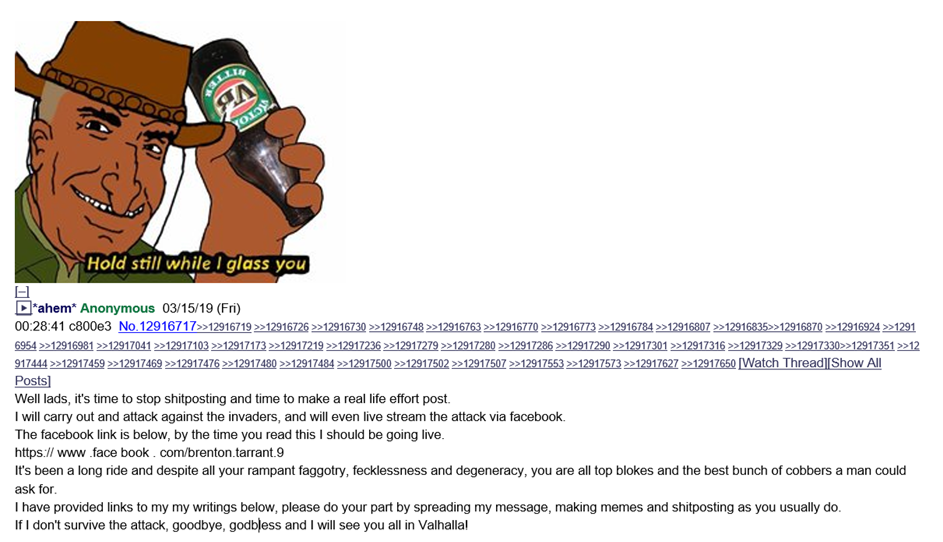

Prior to the attack, at 1.28 pm local time, the assailant posted the anonymous message below onto the now banned imageboard, 8chan. Subsequently, this started a thread with other 8channers [as users of the site were called] commenting below the original post, often interacting and communicating with one another. This holds similarities with wider collaborative/online gaming scenarios such as Twitch, where people can live-stream themselves playing games, where their audience can interact with them or each other in real-time.

The thread also contained a number of gaming cultural overlaps which contributed to the gamification of the attack. One of these prominent gaming features, used 36 times within the thread, was the phrase Press F or just the letter F. Press F to pay respects first emerged in 2014 within the FPS game Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, and was an interactive element where players of the game had to touch a casket at a funeral to pay respect as featured in the opening scene of one of the missions. The 8chan thread was also littered with additional gaming narratives, from pictures, to quotes, to obscure cultural references. One user even asked if this is “Hotline Miami 3 confirmed?”; a reference to the long-awaited sequel of the Hotline Miami series, a top-down violent indie game [one produced by a smaller firm] where the main character(s) enter different buildings and kill all they encounter using a variety of weapons; of course, holding distinct similarities to the Christchurch attack that was unfolding before them.

Points, badges, and leaderboards

The attack was further gamified within the 8chan thread, demonstrated in the form of prestige attributed to achieving ‘high scores.’ Those commenting on the original 8chan post were visibly keeping count of the number of kills and were even challenged by one spectator to “GUESS THE BODY COUNT,” which other posters responded to with “I’m gonna go with . . . . 31,” “I count at least 22 plus the first one on the way in.” One user even uploaded a picture of a chart – originally posted on 4chan a number of years ago and subsequently updated as new incidents occur – of mass shooters, and asked “where will he fit in[?]” The chart included pictures of the shooters, resembling a Top Trumps style approach where it rated them based on how many adults and children they killed, provided extra points if the shooter committed suicide after the attack, and further bonus points for having (perceived or otherwise) various psychological issues, including autism and schizophrenia.

A Framework for Future Attacks?

What remains unclear is whether the Christchurch assailant intentionally gamified his attack as a strategy to, amongst other reasons, inspire future attacks or whether it was more of an organic endeavour due to his fascination with video gaming. What is clear within the data, however, is that there are several gamification parallels within various far-right violent extremist attacks across history. Going back, it is thought the Christchurch assailant was, to some extent, inspired by Anders Breivik’s attack in Norway in 2011. Similar to the Christchurch incident, it is believed that Breivik had gamified elements of his attack and was a keen gamer himself. Moving forward, only a relatively short time after the Christchurch attack, subsequent incidents have demonstrated distinct gamification-related similarities (including, for example, FPS-style live-streams and gaming cultural references, amongst others). These incidents include an assault on a synagogue in Poway, California, in April 2019, an ethnically-motivated attack inside a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, in August 2019, a mosque in Bærum, Norway, also in August 2019, and an attempted attack on a synagogue in Halle, Germany, in October 2019. Many of the perpetrators, predominantly within their own manifestos, even mentioned the Christchurch assailant as a source of inspiration.

However, much of the evidence appears to be anecdotal in nature, as expected for a new and emerging topic of study. Further empirical investigation is needed to determine the potential (or lack) of gamification as a tool to radicalise, recruit, and motivate acts of violence. Is gamification alone enough to inspire attacks of violence, or must other aspects that have traditionally been considered within examples of radicalisation and/or violent extremism be present? What is evident within existing literature is that there are differing ideas about the role and value gamification can play within the context of violent extremism. Many point out its value, though appropriately throw caution by observing that there are wider reservations and criticisms aimed at the concept, including an overestimation of its effects. Further, other authors outline that although it is broadly accepted that gamification can impact behaviour, how this is achieved is still debated.

In reality, although gamification alone more than likely will not be enough to motivate people to engage in violent extremism, it can play some, possibly quite important, roles including: publicising the attack to a wider audience; appealing to a wider and potentially younger audience; enabling people to blur boundaries between the real and virtual world; or having “a cumulative continuum of “collective” extreme-right violence.” What is clear is that the study of gamification within the context of violent extremism is very much in its infancy. Due to the growing popularity of gaming, it can be reasonably argued that gamification and associated concepts can play an increasingly prominent part in future attacks.

The author is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Sussex and a member of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN). He tweets at @surajlakhani.

This article was originally published as a GNET Insight on 10 June 2022.