Esports is a high-growth industry with sociocultural and economic influence. As with any social, cultural, and economic force, emergent and structural issues create conditions that can be exploited for non-aligned and malign purposes. Esports spaces are far from unique in this regard and offer a fertile hotbed for extremist ideologies to take root among young people from an early age. Such efforts may pay deep returns in radicalisation outcomes throughout lifespan development.

At present, it is critical to recognise the threats that emanate from esports communities, identify opportunities for intervention, and act with intent and foresight to remedy underlying malignancies. This Insight presents an overview of the conditions colouring the esports industry, explores areas within which extremist ideologies exist, and describes the United States Esports Association’s efforts to address radicalising processes before they lead to non-peaceable expression.

What are Esports?

Esports are a subset of the video game ecosystem and can be simply understood as video games played competitively in the presence of sports-like structures. Formal definitions for esports vary, although a foundational definition was proposed in 2006 by Professor Michael G. Wagner: “‘eSports’ is an area of sport activities in which people develop and train mental or physical abilities in the use of information and communication technologies.”

This definition is beneficial for two reasons. First, it relies on non-video game domains to form an understanding of the esports domain. This reliance ensures that the study of esports is accessible to experts in any domain and is not constrained to present or historical conditions. Second, this definition presents esports as a synthesis of pre-existing activities, not a thing unto themselves. This synthesis is especially useful today since the literature on esports is greatly underdeveloped, especially in niche areas like extremism studies.

Despite particularities, common sporting phenomena are present in esports. Esports are young, with foundations in the Intergalactic Spacewar Olympics in 1972 and the National Space Invaders Championship in 1980. This relative nascency means that the infrastructure supporting the esports industry overall is underdeveloped and constantly changing, so comparisons with traditional sports must be made through a historical lens rather than how the two spaces exist at present.

Many models of the ecosystem exist, and their utility depends on context. One popular and accessible model was published by Nico Besombes in a 2019 Medium article. This model mirrors the traditional sports ecosystem where internal entities, like teams and leagues, emerge from the intervention of external entities, like players and sponsors, to create sporting entertainment products suitable for fans. This model also suggests that esports are influenced by non-endemic stakeholders, like game developers, whose influence straddles other, related domains, like video games. The complex interactions of the parts of this ecosystem offer unique vectors of radicalisation and mobilisation which have not been explored in the esports context but are studied for traditional sports and video games. Further research is needed in this area.

According to market research firm Newzoo, the global esports audience is rapidly expanding, with an 8.7% annual growth rate, reaching an audience of 640.8 million people by 2025. Esports enthusiasts are predominately men (66%) aged 21 to 35 (31%). Occasional viewers are fairly similar to enthusiasts in gender (63% men) and age (28% between 21 and 35). As with traditional sports, demographics vary by region and game, with Asia having the largest audience.

Esports’ relatively young audience presents concerns based on young people’s exposure to anti-social elements throughout the esports ecosystem. These elements include homophobia, transphobia, racism, sexism, genderism, ableism, antisemitism, Islamophobia, and toxic masculinity. These developmental artefacts have prevailed and become embedded into videogame spaces. Due to an underemphasis on eradicating these ideologies within esports spaces, they exist in scripted and systemic ways in gamer culture.

Online Radicalisation

As online natives, gamers interact over multiple platforms simultaneously, using sites like Twitter (now X), dedicated platforms like Discord, and in-game communications functionalities. As a result, organic and strategic radicalisation and participation in extremist ideologies occur as they do online in general.

Irrespective of use, the internet may pose a greater risk of behavioural radicalisation of users than other sources. This observation increases the impact of risk factors for online natives, like gamers, who may encounter radicalising content more often because of how much they use the internet.

Based on the six-part typology presented by Lamphere-Englund and White, the extension of esports communities across multiple online platforms may place participants at particular risk of encountering everyday extremism organically through emergent gamification, pop culture, and in-game communications. Once encountered, strategic top-down and bottom-up efforts may funnel at-risk participants into less-than-public spaces designed with the intent of radicalisation.

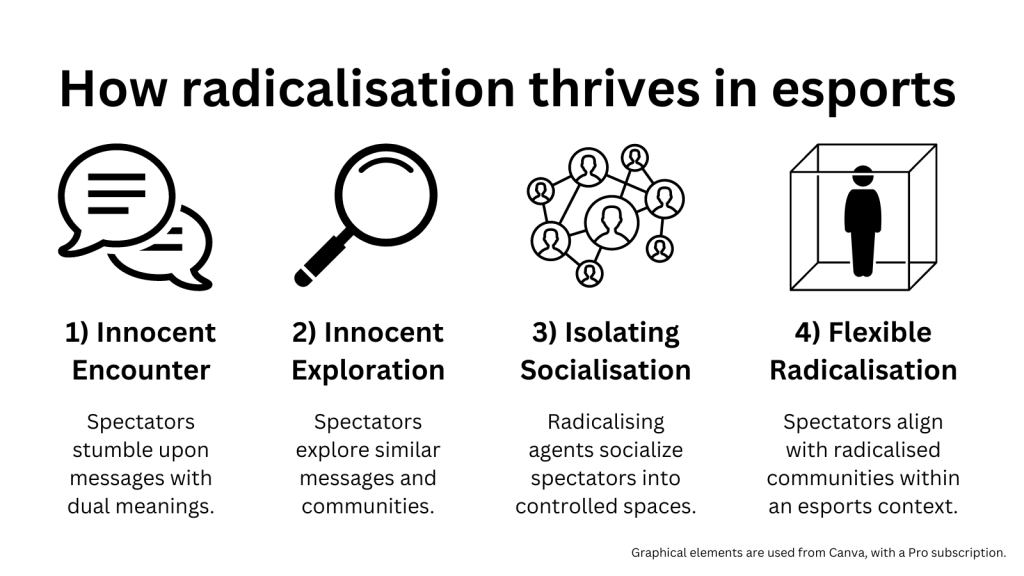

Engaging with radicalising content online ideologically influences decision-making and facilitates radicalisation and mobilisation. As people navigate online spaces and encounter radicalising content, they may self-radicalise by entering a ‘pipelining process’ of normalisation and acclimation to extremist ideologies and the dehumanisation of an ideological target. The use of incrementally controlled spaces may accelerate these processes as a form of isolation. Conversely, these spaces may serve a socialisation function critical to radicalisation by co-opting group dynamics in service of radicalisation, where radicalisation subverts group identities by fostering an us-not-them mentality.

To effectively radicalise bystanders, malign actors have considerable flexibility in how digital content is created and communicated, which may enhance the effectiveness of the pipelining processes. Enhanced flexibility means that content can take on both a surface-level and a hidden meaning. The hidden meaning behind seemingly innocent topics serves the purpose of radicalisation, while the surface-level meaning obscures the radical intent. This flexibility allows for a range of content catering to different levels of extremism, presented in various formats. Users can easily access spaces offering different combinations of content and degrees of extremism.

Esports Radicalisation

In the esports context, an innocent spectator may encounter a surface-level message about a player, team, or game that communicates a hidden message about race, gender, sexuality, religion, or other characteristics. That message may be communicated on a game livestream or on social media. The spectator may agree with the surface-level message and actively engage content and its creator without knowing the hidden message. Over time, the spectator may seek out a community with likeminded people, where they bond over this content in private Discord servers and on Twitter. As community bonds grow, so too do opportunities to direct people to other servers that offer increasingly radical ideologies, while the esports overtones of the relationship need not change.

This risk is compounded by the ecosystemic breadth of esports, as per the Besombes model, which expands the opportunities for radicalisation and decreases the reach of any one stakeholder’s protective factors against it. As someone becomes more engaged, their risk factors grow.

There is no single onboarding process for entering into esports, and esports rely on unwritten rules about the right conduct in its spaces. Instead of a unified process, people self-navigate the space. As they self-navigate, new entrants into esports are confronted with extremist meta-narratives, sometimes through esports celebrities, that parrot the anti-social components of gamer culture. As a person acculturates to esports norms, they tend to adopt a gamer identity as a form of socialisation and identity fusion, which is one way extremism persists in esports.

Having any sense of identity poses risks and benefits, but socialisation to an anti-social community is always negative, even though socialisation itself is beneficial. Over-identification can be similarly negative. Traditional sports offer a useful analogy for how this process works. A 2021 report to the European Commission found that sports offer recognition, fraternity, and identity-making for participants, which facilitate radicalisation when paired with extremist ideologies. Radicalisation in sports also leads to violence in the form of hooliganism, which is analogous to trolling online.

If it is known that one phenomenon (hooliganism) can lead to violence, then it is imperative to address the other (trolling) before it can follow suit. This applies to all forms of extremist expression in esports. It is also unclear whether a distinction between online and offline experience is meaningful or if all experience is blended. With a more blended experience comes increased risk. Coupled with the flexibility of digital and online spaces, esports have immense potential for radicalisation.

Esports as a CT/VE Intervention

Like traditional sports, esports can be beneficial for participants despite risk factors. Repeatedly, the literature describes benefits such as enhanced fine motor skills, perceptual-motor skills, cognition, neuro-cognition, and perceptual-cognition skills, cardiovascular health, mental health, identity development, personal development, and experiences of playful consumption. It is possible to leverage these benefits to equip players and spectators with the skills necessary to combat extremist narratives in esports spaces.

In 2022, the United States Esports Association began developing a National Esports Honors Society,* which is a project funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships. This program targets four areas of competency-building for college students in esports: media and information literacy, peer and intergenerational mentorship, community and civic engagement, and professional development. For a CT/VE context, competency in these areas lays the foundation for combatting extremist activity without infringing on the right to peaceful expression. In the esports context, these areas address deficits in the industry and align engagement with esports to pro-social ends.

For media and information literacy, the United States Esports Association is developing two initiatives: EsportsAccelerate and EsportsHack. EsportsAccelerate is an accelerator program designed to train students in media and information literacy in relation to esports innovation. EsportsHack is the culmination of the accelerator and has students compete against each other in a pitch competition. These programmes gamify learning for media and information literacy and prepare students to encounter potentially mobilising content and to make decisions in a structured and reasoned way.

For peer and intergenerational mentorship, the United States Esports Association is developing EsportsMentors – a semester-long structured mentorship programme to place students in dialogue with their peers and industry professionals. This programme aims to expand participants’ social capital to hedge extremist vectors based on isolation. Students will also be prepared to rely on trusted colleagues within the industry through rapport-building and interpersonal accountability to engage and combat antisocial behaviours.

For community and civic engagement, the United States Esports Association is developing two initiatives: EsportsGiving and EsportsVote. Both programmes educate students on identifying opportunities for community and non-partisan civic engagement and assessing how their skills may be used. As a component of participation, each semester, students will either create or participate in one community service or non-partisan civic activity of their choosing.

Finally, for professional development, the United States Esports Association is developing DiscoverEsports – a programme comprising training and informational materials administered in virtual workshops. The training materials intend to inform support services professionals on career pathways in esports, and the informational materials intend to provide frameworks for internships based on esports competencies. This programme prepares students to assess their professional competencies and match their skills with careers while preparing support staff to work with collegiate esports players.

Conclusion & Moving Forward

As CT/VE work in esports is a new endeavour, there must be a focus on institutionalising robust defences of civil rights and civil liberties. Wherever discrimination lives within esports, the industry must enhance and defend protections for gamers to ensure cross-industry resiliency. The protection of the right to free expression cannot be neglected, and CT/VE interventions cannot overstep the law.

Balancing bona fide interests in suppressing illegal or deleterious speech with protected free expression can be achieved when the focus of interventions is not on ideologies but behaviours leading to mobilisation, which can construct natural barriers against the illegal repression of gamers’ voices. Further development must be placed on creating theoretical frameworks of extremism in esports that incorporate civil rights and civil liberties.

Collaboration and authentic engagement will drive all positive developments in this space. Ensuring collaboration is fruitful while upholding civil rights and civil liberties must be the way forward and can catalyse others to do the same. Our young people’s future depends on it.

Eliot J. Oreskovic is an Executive Co-Director of the United States Esports Association, which is a member of the Extremism and Gaming Research Network (EGRN). This piece was originally posted via an EGRN partnership with GNET accessible here.

* This project is funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships, opportunity number DHS-22-TTP-132-00-01.