Introduction

Since the livestreamed attacks in Christchurch, Halle and the US Capitol Building, streaming platforms have become a topic of interest for radicalisation studies and efforts to prevent and counter (violent) extremism (P/CVE). These livestreamed acts of violence are just the tip of a barely explored iceberg of extremist activities on streaming platforms. While existing studies point to extremist activities on various video and streaming platforms, systematic research efforts into these activities are still lacking.

The RadiGaMe project, implemented by a German Research Alliance consisting of eight research institutions, civil security institutions and civil society organisations, seeks to contribute to closing this important research gap. In the first stage of the project, we conducted a first-impression analysis of 20 gaming and gaming-adjacent digital platforms to gain insights into their functionality, relevance for extremist actors, access options for researchers, and the type of extremist and fringe content posted in these digital spaces. This EGRN-GNET Insight reports the results of our exploration into eight video- and streaming platforms. The Insight is based on a German report that can be accessed here.

The Landscape

Livestreaming is on the rise. While only a few platforms dominated the market in the past and enabled live streaming, today, there are a greater number of platforms with various policies. Recent studies indicate that extremist actors also appear to be active on live-streaming platforms, which is why we have subjected the following platforms to a first impression analysis.

In the following Insight, we classify platforms into original platforms and alternative platforms for structural reasons. We define original platforms as those platforms that represented a fundamental innovation and paved the way for further alternative platforms. Due to their size and reach, these platforms are often at the centre of social attention and have attempted to moderate content across the board, even if this is not always successful. In terms of infrastructure (functionality, user experience, and more) alternative platforms are closely orientated towards the original platform. The alternative platforms presented here are characterised by a high incidence of radicalised communication dynamics and usually only contain a minimum level of content moderation.

The general aim of the analysis was to create an overview of various platforms, their functionality, their role in the gaming ecosystem, and their potential significance for extremist actors. We also examined the potential physical and ethical barriers and access options for researchers in this field. In addition to investigating what is already known about the platforms, we conducted keyword and profile searches to encounter radicalised communication.

After the first impression analysis, we will conduct an in-depth analysis of radicalised communication on gaming and gaming-adjacent platforms.

While conspicuous material was found on all of these platforms, our exploration revealed that they are not equally relevant for radicalisation research. The following part will give an overview of some of the examined platforms:

Explored platforms with strong gaming-reference:

Twitch, DLive, Kick

Explored platforms with secondary gaming-reference:

YouTube, BitChute, Rumble

Twitch, DLive, Kick

Twitch, DLive and Kick all have clear links to the gaming community and contain a large amount of gaming-related content. For instance, there are streams focused on specific games such as Grand Theft Auto V, Minecraft, or Counterstrike. However, these platforms also host a large amount of content related to various other topics – from sports and music to lifestyle and cooking content. The category of streams with the highest reach is “Just Chatting”, in which streamers talk about all kinds of things that might interest them and their audience. It is not uncommon for socio-political topics to be discussed here.

Twitch is the streaming-platform with the highest relevance in the gaming-sphere and the largest user base. Despite the platform’s well-known moderation efforts, we located racist statements, content espousing trans-homophobia and queerophobia, as well as content promoting narratives of the new right, such as remigration, the ‘Great Reset’ and ethnopluralism during our exploration. In addition, we examined the active promotion of right-wing propaganda games. For example, at the time of the exploration, a gaming influencer who belongs to the far-right scene surrounding the identitarian movement promoted a new video game from the German far-right developer Kvltgames. The comment sections of these streams contained misanthropic, racist, misogynist and antisemitic comments. For instance, commentators called immigrants “vermin” and threatened women with rape. We also found that blocked individuals re-appear on the streams of other right-wing streamers and are, therefore, still able to spread their messages. This has been observed with Martin Sellner, head of the Identitarian movement and officially blocked by the platform, who gave a 2-hour interview to a far-right influencer. Similar practices have also been identified among other influencers. Although Twitch implements comparably strict and effective moderation measures, we nevertheless deem the platform relevant for extremism studies as we could locate hateful and extremist content with relative ease.

A right-wing influencer playing and advertising the new game by the German game developer Kvltgames.

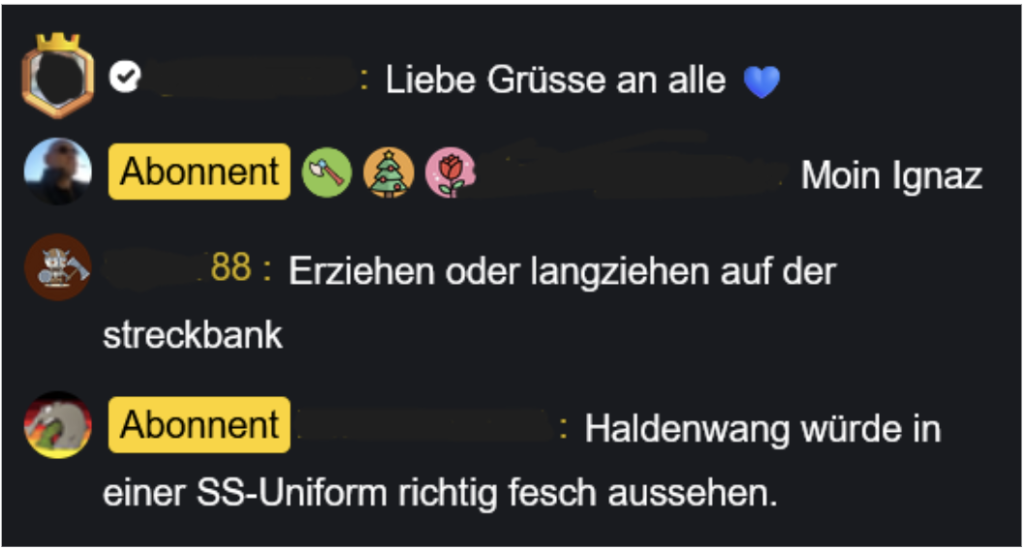

DLive was founded in 2017 as an alternative to Twitch and YouTube. Both current research and media reports demonstrate that DLive hosts an abundance of right-wing and far-right streamers spreading antisemitic and racist content, disseminating conspiracy narratives, popularising narratives of the incel- and manosphere, and even, in some cases, inciting hatred and violence. We have observed both open displays of hateful ideologies as well as camouflaged language and dog-whistling, such as the use of code words only people ‘in the know’ understand as ideological terminology. Although the platform’s community-guidelines prohibit explicitly the use of hate speech and the spread of violent content, there is little effort to prevent or avoid this kind of content. At the time of the exploration, right-wing extremist codes such as “14 words” or “88” could be found openly in profile names, comments and streams. 14 Words and 88 are frequently used slogans by white supremacists. 14 words stands for the racist dogma: We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children and 88 is a cipher for twice the eighth letter in the alphabet (HH – Heil Hitler). Similarly, we’ve observed the use of terminology related to conspiracy narratives, antisemitic tropes, and references to Nordic and Germanic mythology, such as the Song of the Nibelungs, which was instrumentalised by German National Socialists before World War II. Even content punishable by German law was located, including hateful comments about German politicians, calling them „rats“ and „flies“ that should be „hanged“, as well as dehumanising terminology directed at migrants and minorities, including that Muslims are a “pest” and “cockroaches”, who “need to piss off and leave (German) women alone.” We therefore deem DLive to be highly relevant for extremism research.

User of DLive using far-right codes in their nicknames, while watching a livestream of a German far-right activist. In the commentary section, they are using threats camouflaged as jokes against politicians.

Kick entered the market in 2022 as a competitor to Twitch and is considered a viable alternative by streamers due to its reach, lax content moderation, and the possibility of high earnings. The high level of connectivity between DLive and Kick is also noteworthy, as streamers often have profiles on both platforms and play on them. We were able to locate a large number of right-wing extremists and conspiracy ideologues on the platform who are able to spread their content more or less unchallenged. These include the Infowars channel run by far-right influencer Alex Jones, various Nick Fuentes fan channels and streams from cadres of the Identitarian movement. Patchwork ideologies are propagated, in which conspiracy narratives about the COVID-19 pandemic, migration and current crises such as the Gaza conflict are mixed up and presented as correlated. These conspiracy theories are discussed in hours of streams. In addition, openly antisemitic and misanthropic comments were found. A user whose profile indicated a National Socialist ideology, for instance, commented, “Even Hitler get more B****** then you, f***** kill these jewish b****” on a stream by a right-wing extremist influencer discussing dating. We therefore deem Kick to be equally relevant as DLive, particularly when researching the dissemination of far-right and conspiracy narratives on a transnational level.

User identifying with the Groyper Movement.

YouTube, BitChute, Rumble

YouTube is the world’s largest video platform. YouTube Gaming was initially launched as a standalone platform in 2015 and was then integrated into the YouTube platform itself in 2018. The platform hosts livestreams and recorded videos, as well as tips and tricks for digital games. Extremist activities on YouTube have been the subject of research for many years, and it is well-known that the platform has inadvertently hosted and recommended such content in the past. Gaming-related extremist content on YouTube, however, has not been the focus of research efforts so far. We therefore created a first-impression analysis of gaming content on YouTube to investigate the intersection between gaming and potentially extremist content on the platform. We found misogynist and racist content, particularly in the comment sections of gaming-related videos and streams. For example, the following comment was posted under a video for a game in which National Socialists won the Second World War: “Cool. I love Nazis, they were sick fighters back then […] wicked [display of] red soup😆😆👍 Death to those left-wing antifa pigs.” The following comment illustrates the misogyny we detected: “WOKENESS, TRANSWOMAN & FEMINISM: KILLS ME!” The platform remains highly relevant in terms of extremism research and the research of far-right movements, as well as Islamist movements. However, we found little evidence of an explicit link between YouTube, gaming and extremist activism.

BitChute is a YouTube-style video platform that hosts a significant number of channels and content that has already been demonetised, deplatformed or deleted on other platforms. It can therefore be described as a fallback platform. The ‘trending tags’ of the platform at the time of exploration were, among others: #PPROPAGANDA, #RUSSIA, #CHINA, #COVID, #VACCINE, #PLANDEMIC, #FLATEARTH. The hashtags suggest a tendency among several users towards conspiracy-theoretical content. We also detected a significant amount of racist and antisemitic content as well as anti-Muslim and anti-Islamic hatred. One commentator, for instance, declared: “You need to kill these muslim invaders, literally you must kill them all.” In addition, right-wing extremist content was found, such as songs by the now-banned German neo-Nazi band Landser and other figureheads of neo-Nazi movements. However, the exploration revealed only a handful of gaming-related channels hosting relevant content. Therefore, while BitChute is generally relevant for radicalisation studies, we deem it less relevant for gaming-related extremist activities than other video- and streaming platforms we explored.

Antisemitic narratives seen on the platform.

Rumble was founded in 2013 and has been linked to right-wing and conspiracy narratives. A recent ISD report, for instance, states that Rumble is one of the top three alternative platforms for the distribution of conspiracy narrative content. The platform mainly seems to attract users from the right-wing and conspiracy narrative milieu. At the time of the exploration, a large amount of content spreading right-wing extremist narratives and antisemitism could be located. This includes posts disseminating narratives such as ‘The Great Replacement’ and ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’, popularising antisemitic stereotypes. We also found content that can be attributed to the manosphere and incel ideologies. In our exploration, we did not find a large overlap with extremist- and gaming-related content. Nevertheless, the mass of radicalised and conspiracy theory content is considerable and recommended for further research in radicalisation studies.

Outlook

Our initial explorations and first-impression screenings have shown that there are clear signs of extremist influence on streaming platforms. While we found relevant content and signs of hateful (potentially radicalising) communication in these digital spaces, our knowledge of the dynamic interaction between streaming content and radicalisation remains limited. The nexus between gaming, streaming, and radicalisation needs to be analysed in greater depth in the future, and important challenges, such as the fleeting nature of livestreams and the difficulty of data collection, must be addressed. The importance of the platforms for further research is also fuelled by the high level of community awareness within the audience. Streamers are able to instrumentalise those feelings of community through various types of communication styles. Consequently, individual spectators can experience a sense of belonging within a larger community of like-minded individuals, potentially amplifying pathways to radicalisation. Based on the results presented here, we deem video- and streaming platforms highly relevant for our contemporary understanding of propaganda dissemination and extremist activities in the digital space, which deserve more attention from researchers and prevention practitioners.

Lars Wiegold is a research associate in the RadiGaMe and RADIS projects at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF). His research focuses on radical and extremist online milieus, particularly in digital gaming communities.

Constantin Winkler is a Doctoral Researcher at the RadiGaMe Project at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF). He investigates antisemitism and radicalisation in digital gaming communities. He focuses on antisemitism research, cultural sociology and Critical Theory.

Judith Jaskowski has been working as a research assistant at modus – Centre for Applied Deradicalisation Research with a focus on games since 2023. She previously worked as a game development manager for various German developer studios.

This piece was originally published via an EGRN partnership with GNET and is accessible here.